Tonb Iranian Islands

Date: 6/26/2015 9:39:12 PM

Tonb Iranian Islands

The downfall of Saddam Hussein has had many implications for the region—not least the ubiquitous retreat of Arab nationalism. This even extends to the cosmopolitan and successful country that is the United Arab Emirates.

Territorial disputes amongst the states that straddle the Persian Gulf have been a perennial feature of the region’s geo-political landscape ever since the retreat of British colonialism from the Middle East.

One of the more enduring disputes revolves around the long-standing UAE claim on three Iranian islands in the Persian Gulf. This dispute-which was mainly sustained by Baathist-sponsored Arab nationalism-- most recently flared up in 1992 and was a major thorn in Iran-UAE relations for five years.

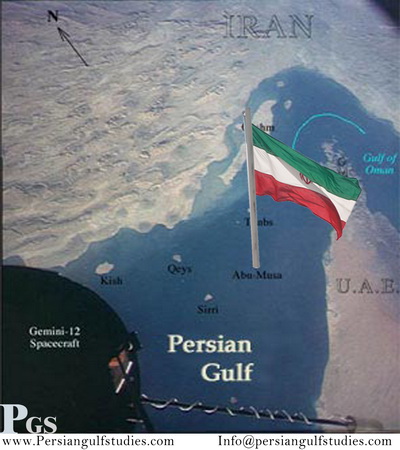

Although the UAE claim on the three islands of Greater and Lesser Tunbs and Abu Musa is no longer pursued with the same vigour by the country’s officials, nevertheless an assessment of the events of 1992 and its historical context will yield a penetrating insight into the geo-politics of the Persian Gulf and the complex process of nation-state formation in the United Arab Emirates.

Furthermore it shows how the destruction of the Saddam Hussein regime could lead to more positive interaction between Iran and her neighbours on the western shores of the Persian Gulf.

The Historical Context

Iranian and Western documents show that the islands known as the Greater & Lesser Tunbs and Abu Musa have historically been an intrinsic possession of successive Persian empires. However the advent of the modern age coupled with rising Arab political consciousness on the western shores of the Persian Gulf seriously undermined the immunity enjoyed by the idea of “historical possession” from theoretical and practical challenges.

The challenges of the modern world forced the Iranian government in 1885 to abandon the old Safavid federative administrative system and introduce a new system of state organisation based on the division of the country into 27 provinces.

The 26th province incorporated the ports and islands of the Persian Gulf. This was a direct attempt by the Iranian government to undermine the autonomy of the Qasemi Sheikhs of Bandar Lengeh. The Qasemis had for generations ruled over the Lengeh and its dependent islands on behalf of the Iranian government. This group of islands included, amongst others, Kish, Tunbs, Abu Musa and Sirri. The Qasemi ascendancy at Lengeh conformed to the federative structure of the Old Persian state and did not undermine Iran’s sovereignty over Lengeh and its islands.

However the pressures exerted by the relentless onslaught of British colonialism and its attempts to create Iranian-Arab friction in the Persian Gulf impressed upon the Iranian side the need to abandon the old federative structure. Indeed as J.G. Lorimer put it in his 1908 Gazateer of the Persian Gulf: “The years 1887 and 1888 were signalised…… by a spasmodic attempt on the part of the Persian government to assert themselves in the politics of the Persian Gulf.”

The Iranian government’s efforts to modernise the administrative system of the country did not deter the British from further encroaching upon the sovereignty of the country. In fact in July 1903, citing fears of growing Russian influence in the Persian Gulf, the British occupied all the strategic islands of the southern Persian Gulf, including the Tunbs and Abu Musa.

In a testament to the internal upheavals gripping early 20th century Iran, it took the Iranian government more than a year to realise the islands had been occupied by British forces.

It is noteworthy that the British occupation forces hoisted the flag of Sharjah in Greater Tunb and Abu Musa immediately after their occupation in 1903, and moreover hoisted the aforementioned flag in Lesser Tunb in 1908.

The occupation of the islands persisted until 1971 when the 150-year British domination of the Persian Gulf came to an end. It is noteworthy that 1971 marked the birth of the United Arab Emirates as an independent nation-state. The British were fully aware that the creation of this state was opposed by a number of powerful Arab countries—in particular Iraq and Saudi Arabia.

Therefore, in an attempt to secure the survival of the nascent UAE, the British decided to placate the historical demands of the Iranian state over the three occupied islands of Greater & Lesser Tunbs and Abu Musa. The British agreed to return the Tunbs to full Iranian sovereignty and moreover insisted on joint Iran-Sharjah sovereignty over Abu Musa. The insistence on joint sovereignty over Abu Musa was a major blow to Iran that had legitimate stakes to full sovereignty over the island.

Furthermore the partition of Abu Musa into “northern” and “southern” zones typified the post-colonial political/security structures that the British left in place in many parts of the world as they hastily abandoned their empire. Whether by design or default the British guaranteed friction and disputes between Iran and the nascent UAE for the next 30 years.

A small party of Iranian naval officers landed on Abu Musa on 30 November 1971 and took control over the northern part of the island as agreed in the 1971 “Memorandum of Understanding” signed by Iran and Sharjah under the auspices of British Foreign Office. The party was officially welcomed by the brother of the Sheikh of Sharjah. Iran also agreed to pay Sharjah (which was to become one of the main constituents of the emerging UAE) £1.5 Million annually for 9 years to ensure the nascent emirate’s economic viability.

The two Tunbs were seized on the same day. However during their landing on the Greater Tunb Island Iranian forces came under attack from the police outpost of Ras al-Khaimah resulting in the death of one Iranian naval officer. The Iranians, who had been widely welcomed in Abu Musa, expected a similar reception in Greater Tunb and were thus sorely disappointed. In later years certain quarters in the Arab world used the incident at Greater Tunb to buttress their contention that Iran had “occupied” the Tunbs. This contention is untenable as not only was the confrontation limited but moreover, it was the result of misunderstanding arising from the failure of the Ras al-Khaimah authorities to inform their outpost of the imminent arrival of the Iranian naval unit.

Re-emergence of the Dispute

For the next 20 years the issue of the Tunbs and Abu Musa was put on the back burner. However it was clear from the start that the islands would inevitably re-emerge as a point of contention between Iran and the UAE. The Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) of 1971 had been a British inspired deal and moreover had failed to fully recognise the aspirations of Iran and Ras al-Kheimah.

In a further complication, there was widespread misunderstanding on the Arab side that the islands of Tunb had been “granted” to Iran as result of the country’s concession over its historical claims on Bahrain. This notion is, at best, a misperception as there is no evidence to buttress it. Furthermore radical Arab states—in particular Iraq—rejected the MoU as a betrayal of Arab aspirations and applied pressure on the embryonic UAE state to reject it. This pressure was kept up throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s.

The only surprising thing is that it took more than 20 years for the dispute to flare up again. In April 1992 it was reported that Iranian authorities were preventing a group of non-nationals from Sharjah to enter Abu Musa. The High Council of the UAE met on 12 May to discuss the latest developments in Abu Musa and announced at the end of the meeting that the individual commitments of constituent members of the Union before 1971 were to be considered as the commitments of the Union in its entirety. This announcement effectively set the scene for a “national” territorial dispute with Iran.

In August 1992 Iran prevented a further 100 non-nationals—the majority of whom were Egyptian—from entering Abu Musa. Iranian media accused the UAE authorities of trying to “Arabise” the population of the island. However the real motives were somewhat more complex and interesting. According to informed sources Iranian authorities suspected a number of regional and extra-regional countries of trying to spy on the country’s military outpost on the island. It is noteworthy that a Dutch national had been arrested in Abu Musa in August 1992. He is believed to have been a former Officer in the Netherlands intelligence services and, at the time of his arrest, was allegedly working for the intelligence services of the ousted Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein. This former Iraqi agent continues to languish in a Tehran jail—testament to how seriously Iran treats the security of its strategic islands in the Persian Gulf.

From an Iranian perspective the unilateral abrogation of the MoU by the UAE was not a particularly serious issue, as Iranian foreign policy faced far more robust challenges from more powerful states. Nevertheless the Iranians, anxious to remove any pretext for the prolonged stationing of foreign—particularly American—forces in the region were more than willing to engage their emirati counterparts.

The conciliatory Iranian position was not helped by the increasingly confident posturing of the UAE. In the autumn of 1992 negotiations between Iran and Sharjah to arrive at a final status for Abu Musa were scuppered by the UAE foreign minister who linked any settlement on Abu Musa to the subjection of the Tunbs to UAE sovereignty. This stance destroyed any prospects for real negotiations.

The Iranian media were sceptical of the motives of the UAE side in re-igniting the dispute. After all, they argued, how could a peripheral player like the UAE, concocted out of the ashes of the British Empire in 1971, have territorial claims on a powerful and historical state like Iran? There was widespread speculation that the UAE had ignited the dispute at the behest of America. It was argued that the Americans needed to stoke up regional tensions to justify their military presence in the Persian Gulf.

The position adopted by the Iranian media, although understandable under the circumstances were nevertheless somewhat unfair. The UAE may have enjoyed tacit support from the Americans in their disputes against Iran, but their claims on the islands owed more to a haphazard grasp of historical facts and events rather than American influence.

From an Iranian perspective the UAE side has consistently failed to put forward a rational and historically grounded argument in favour of its claims on the islands. A vivid example is a statement made by the UAE Foreign Minister at the UN General Assembly in September 1992 in which he claimed that the Tunb islands and Abu Musa had belonged to the emirates “since the beginning of history.”

It is interesting to note that the tribal entities of Sharjah and Ras al-Kheimah were created in 1864 and 1921 respectively and moreover the modern state of the UAE was christened in 1971.

The core arguments put forward by the UAE side essentially revolve around a number of correspondences exchanged between the Sheikhs of Sharjah and Ras al-Kheimah, British political representatives and the Qasemi Sheikhs of Bandar Lengeh.

In his Security and Territoriality in the Persian Gulf –which is widely regarded as the best piece of research into the territorial disputes of the Persian Gulf— Pirouz Mojtahed-Zadeh subjects these letters to a critical appraisal and makes a number of interesting observations.

One of the letters usually cited by UAE officials is a correspondence dated 29 March 1884 and from Sheikh Yusof al-Qasemi of Lengeh (i.e. representative of Iran) to Sheikh Hamid al-Qasemi of Ras al-Kheimah, in which the former announces that the: “……island of Tunb actually or in reality is for you”. The UAE side interprets this letter literally and concludes that the Qasemis of Lengeh were in fact transferring sovereignty of the Greater Tunb to Ras al-Kheimah. However, as Mojtahed-Zadeh observes the notion that “it is for you” merely constitutes a standard Middle Eastern courtesy and compliment designed to sweeten relations. It in no way implies the transfer of land and riches to the other side.

In any case a few lines below the statement pertaining to Greater Tunb, Sheikh Yusof al-Qasemi states that: “……the town of Lengeh is your town”. Clearly the high official of Lengeh is unlikely to voluntarily cede a major Iranian port town to a foreign entity.

Apart from the lack of any credible historical evidence to support the UAE case, emirate officials also made a number of dubious claims that seriously undermined their cause. In October 1992 the UAE announced that Iran had “occupied” the entire Abu Musa Island. This was untrue as visitors to the island have testified that symbols of UAE sovereignty—in particular the national flag and a police outpost—are still visible in the southern part of the island.

The UAE case unravelled further in a round table discussion between Iranian and Arab academics in London in November 1992. Apart from the academics, 22 Arab ambassadors were also present at the meeting. In the meeting, Dr. Pirouz Mojtahed-Zadeh, who is widely recognised as the foremost expert on the affairs of the Persian Gulf, produced 24 maps, mostly belonging to the British government in the latter half of the 19th century,that proved Iranian possession of the islands. Prior to the round table meeting it was widely believed that only a single official British map, produced in 1886, clearly recognised Iranian sovereignty over the islands.

The UAE tried to internationalise the dispute but all the major powers expressed neutrality over the issue. Even the Arab states were unwilling to lend diplomatic support individually and only lent moral support collectively in the form of the (Persian) Gulf Cooperation Council and the Arab League. The only exception was the former Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein that, true to its ultra-nationalist ideology, lent significant support to the United Arab Emirates.

The UAE scholar, Mohammad Abdullah al-Roken in his Dimensions of the UAE-Iran Dispute over Three Islands hints at the limitations of the UAE stance by candidly stating that the UAE: “as a small state, aware of the imbalance of power with Iran, and the absence of a deterring force, whether regional or international….hopes that the development of good relations will inevitably lead to the settlement of the contentious problems.”

Indeed the UAE has not been pursuing the islands case with any seriousness since 1997. The main reason has been a lack of interest among major powers to back the UAE position. Moreover the visit made to Tehran by the UAE foreign minister in 1997 led to an immediate thaw in bilateral relations, and contrary to what al-Roken predicted, instead of leading to a bilateral settlement has resulted in the virtual abandonment of the dispute by the two sides.

Conclusion

It is tempting to pour scorn on the follies of the UAE government over the past 30 years in pursuing a hopeless territorial dispute with a much more powerful state that boasts several millennia of political history. Moreover it is easy to criticise the Iranian government for not seriously addressing the issue, and instead relying on Iranian academics to defend the country’s position.

However the pursuit of this hopeless case must be set in the context of nation-state building in the United Arab Emirates since 1971. The UAE has been anxious to define and consolidate a distinctly Arab identity for its citizenry.

This identity-formation project has at times been taken to extremes as Abu Dhabi officials displayed a propensity to be influenced by the Baathist ideologues of Baghdad. It is interesting to note that the UAE has, throughout its short history, experienced pressure from the former Iraqi regime to confront Iran over the three islands. Hence, the ouster of Saddam Hussein in April 2003 may in time mark an end to territorial disputes between Iran and the UAE over the Tunbs and Abu Musa.

But the resolution of this dispute will not necessarily end the identity crisis of the emirates. While it is true that globalisation and the emirates growing expatriates community have given cities like Dubai a remarkably cosmopolitan flavour, nevertheless the UAE still likes to tout itself as a bastion of Arabism.

This might be at odds with the ethnic make up of the emirates. Iranians continue to make up a significant constituency in the country. In fact according to some studies up to 70-80% of the emirates’ indigenous population are of Iranian origin.

Broadly speaking there are three “types” of Iranians living in the emirates. One segment includes the Iranians who settled on the western shores of the Persian Gulf during the Sassanid period over 2000 years ago. This constituency became Arabized over time, but in some cases still continue to display cultural peculiarities that give away their non-Arab origins.

The second type is made up of Iranian immigrants who flocked to the emirates during the Safavid period in the 16th century and thereafter. This type has also become largely Arabised. Nevertheless it is interesting to note that according to reliable sources the al-Qasemi rulers of Sharjah and Ras al-Kheimah are originally from the Bandar Abbas region in Iran.

The third type includes immigrants from the latter years of the Qajar period. Many of these people, although Arabised on the surface, continue to nurture an Iranian identity. On top of these three types must be added the tens of thousands of Iranians who have flocked to the emirates—in particular Dubai—over the past 50 years.

Given the influence of Iranians and Iranian culture on the historical evolution of the tribal Sheikhdoms that coalesced to form the UAE in 1971, bogus territorial disputes peddled by certain quarters in the region are, at best, an exercise in puerile geo-political games.

| loanemu.com | ۱۳۹۴/۰۷/۲۲ | |

| Im obliged for the blog article. Cool. | ||